Q+A: A 9/11 health advocate talks LA fires

Lila Nordstrom discusses short & long-term health risks, what to expect next

Lila Nordstrom was a senior at Stuyvesant High School when the World Trade Center fell, mere blocks from her school. In the weeks, months, and years that followed, she and her classmates became part of a cohort of people who developed short and long-term health issues from breathing polluted air. This week, I sat down with Lila—who now lives in Los Angeles—to learn more about her experience navigating chronic health issues post-9/11 and advocating for others who experienced these harms.

Fi Lowenstein: It’s nice to be with you—virtually. Can you start by telling us how you came to be a 9/11 health advocate?

Lila Nordstrom: I founded an organization called StuyHealth that does advocacy for the youth that were exposed to the World Trade Center cleanup after 9/11. I'm a 9/11 survivor who attended high school three blocks from the World Trade Center, and [my school] was the first to return to the exposure zone in the aftermath of the attacks. So we were exposed to a lot of the same stuff [as] the first responders.

FL: Is it true that more people died from health complications post-9/11 than died in the actual attacks?

LN: Yes, that is true. When you take the entire 9/11 community as a whole, the number of people who've died of 9/11 related illnesses dwarfs the number of people who actually died on the day. I think just under 3,000 people died on 9/11 and I think the current estimate is 6,500 people have died of 9/11 related illness since the attacks. That, of course, only includes the people who have been able to self-identify as having died of a 9/11 related illness. Plenty of people either don't find out in time, or never make the connection.

FL: Can you tell us what was it was that made people sick?

LN: The main dangers in the post 9/11 era were the dust itself—which was essentially a pulverized building that was flying through the air. So that's pulverized concrete, but also asbestos, lead, mercury, silica, cadmium, and a bunch of carcinogenic chemicals—also a lot of chemicals we never really found out about.

But, there were also very high levels of dioxins and other fire chemicals, because the fires at Ground Zero burned until late January, and the community came back long before that. There were hundreds, if not thousands of chemicals in that dust, and we have not identified all of them.

At the time, the federal government and the city government were telling us that the air was safe to breathe.

I think people have the impression that everyone was in the dust cloud, and that's how everyone got sick. Most of us that got sick from 9/11 were never in the dust cloud. I was never in the dust cloud. I never got coated in white powder, like those images that you see. But, me and my classmates still got sick because we got exposed to the fire that burned for a few months. We got exposed to the secondary dust that made it into our school's air system and landed on us on a daily basis. A lot of people might not have even been there on 9/11 and still got sick. People didn't really have any experience with this kind of environmental exposure, and so kind of just went back downtown and cleaned up their houses, and resumed their lives, and spent months in the exposure zone breathing in these chemicals. That was how a lot of the exposures actually occurred in the aftermath of 9/11.

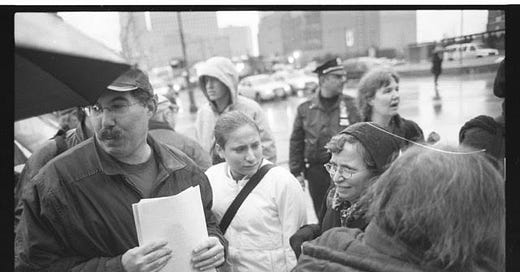

[a Black and white image of Lila as a teenager in downtown Manhattan]

The cleanup operations also caused dust to migrate around the community. There were numerous cancers among people who worked at Fresh Kills, which was the landfill they were taking all of the debris to from the site.

FL: Do we have a sense of how long these chemicals can last in our environment and how far they can travel? I’m remembering the Canadian wildfires in 2023 caused horrible air quality in New York City—that’s a lot of mileage for particulate matter…

LN: I don't think that we have a good way of predicting what will happen in terms of how long these exposures will be present in LA. A lot of it is weather and atmosphere dependent. I think a good rule of thumb is, if you can smell smoke, you're in the danger zone. If you can see the air, or see ash around you, you're in a contaminated area. It's not necessarily that the air itself is contaminated, but the wind can blow contaminants.

It's not going to rain for a long time in LA. So, there's going to be recontamination. The air should clear out itself a few days after the fires burn out. But, these fires don't burn out just because they're contained. I think there's a misunderstanding about how long it actually takes to put these kinds of fires out. The containment is when it stops burning down people's homes, and that does improve the air quality just because there's not petroleum burning as part of the smoke, but the fires themselves will probably keep burning for quite a while. So, we may have incidents where smoke blows into town, depending on which way the wind is blowing, and we have to be kind of vigilant about that. In general, if you are in LA and you've not heard about a fire happening, but you smell smoke, you should put on a mask.

FL: So, it sounds like we’re going to be looking a lot at the forecast for wind in the coming weeks and months? What else should we look out for?

LN: I think once the fires themselves burn out, the real concern is in cleanup zones, and that may include people's homes that weren't on fire, but were near fires and have soot and other [contaminants].

It’s not going to be like 9/11 where there was a very small area with a huge amount of debris that had to be cleaned up over the course of months. I think LA, at least, has the benefit of being much more spread out. It’s not like the the level of contamination per burn site is going to be quite the same, but I think people will have to be thinking about multiple kinds of exposure. They'll have to be worrying about what the air smells like, what AQI is telling them, but also just what their senses are telling them about the air—and then also worrying about physical contamination during cleanup processes. Because, that's going to obviously take a really long time.

FL: Let’s talk a little bit about health concerns in LA—what are your primary concerns for the short and long-term?

LN: I think the health concerns are the exact same health concerns that started after 9/11.

They sound minor in the moment, but if you have headaches, you're having breathing trouble, you have a cough, or you're getting nosebleeds, you're getting a level of exposure that could open you up to a long-term health risk.

There's two buckets of health concerns that result from this kind of an event. There's the short term stuff, which you would expect: people with asthma are not happy right now, people are getting headaches, people are developing coughs and other kinds of respiratory issues or sinus-related issues. Then, there's this second bucket of health conditions that have longer latency periods, that are more serious, like cancers [and] autoimmune disorders—the illnesses that broke open the 9/11 health conversation.

Initially, we all were sick after 9/11. No one who was living, working or attending school in the exposure zone was feeling great in the months after the attacks. It was a few years later when people started getting cancer, though, that we started discussing, oh, are we going to die of these illnesses? When you start feeling those early onset indications that you are breathing in too much smoke, you should do your best to mitigate your exposure, not just because you don't want to have asthma in the short-term, but because you want to mitigate the risk that you will develop a cancer later on.

FL: I understand you were forced back to school very quickly after 9/11. Why might a speedy return to “normal” be ill-advised?

LN: I think I would encourage everybody to not fall into the trap of thinking that a return to normalcy is more important than their health. It's word for word why we were told we had to return to [school] so quickly. We returned less than a month after the attacks. It was obvious it wasn't safe, but there was this impending sort of panic that if we didn't get back to normal soon, our development would be stunted and we would never be able to do anything ever again.

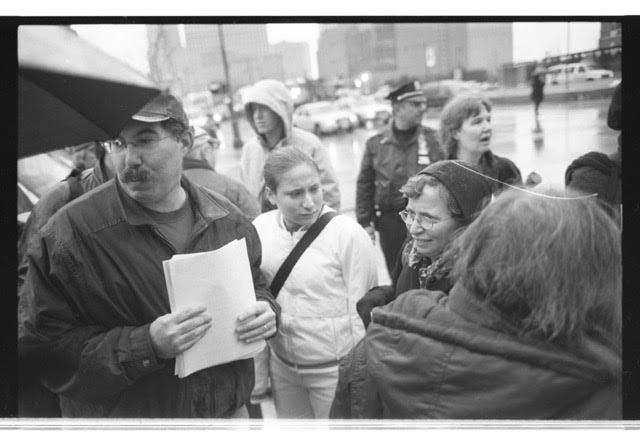

[a press clipping featuring Lila’s work as a 9/11 health advocate in 2006. The headline reads: Stuy grads’s 9/11 dust crusade: Five years later, health coverage concerns linger in the air for elite school alums.]

After a crisis, [people] are desperate to regain some form of normalcy. That is going to happen after these fires as well. LA is going to be forever changed by this experience, and people are not going to be in a place where they can really admit that to themselves right away. But, your physical health is more important than your routine. If that means being the only person in your office or school that is wearing a mask all day every day, then do that.

Don't go back to a place that that you don't feel is safe. That is what I wish that I had known on 9/11. I wish I had known about the concept of PPE. No one ever even mentioned masks. No one mentioned air purifiers.

The problem with a disaster is you don't get to go back to normal. It's not how it works. It’s too bad—we'd all love to, but if you just admit to yourself that it's probably not going to be normal ever again, and you will find a new normal, then you become a little bit more resilient to some of the changes.

FL: Last question—this is the second time in your life that you’ve watched a city you’ve lived in for close to two decades be fundamentally changed by a huge environmental hazard. Do you have any thoughts about how to get through what comes next?

LN: I think the thing that really enabled me to get through that experience in New York was that I got involved in advocacy.

I think finding a way to proactively be a part of rebuilding the city is critical—even if you don't think of yourself as the kind of person that gets involved. It puts you in touch with the community that still exists.

You can feel very much like your your hometown disappeared when something like this happens, because the the feeling in the air changes. A lot of people leave, other people come. There's usually developer vultures that try to ruin everything. There are a lot of things that I don't necessarily look forward to for LA right now, but I also think that if you don't get involved, then you don't get to be a part of retaining what is really great about the community that you live in. When you're organized with the people that care about a place, you can protect the place from other people that don't care about it.

Doing advocacy around the 9/11 survivor community put me in touch with other people that had experienced this with me, who were also invested maintaining some sort of like semblance of community in the aftermath. I think that will be really important in Los Angeles.

Lila Nordstrom is the founder of StuyHealth, an advocacy group representing former students who were in lower Manhattan during 9/11 and the resulting cleanup. She is the author of the book, Some Kids Left Behind: A Survivor’s Fight for Health Care in the Wake of 9/11. She currently lives in Los Angeles. You can follow her on Instagram @lilainchelsea.