I alternatingly pride and chide myself on my propensity to plan ahead. It’s a blessing on a group vacation, and a nightmare when I’m trying to fall asleep before a big day. And yet, despite my diligent meal prepping, color-coded calendar, and meticulously managed to-do list, there is one area where I have historically struggled to get my shit together: planning for climate and related disasters.

I’m not a complete mess. I stockpiled water for my car and apartment when I first moved to Los Angeles, and my love of camping means I’ve got a substantial amount of gear that can be repurposed for both evacuating and sheltering in place. But, I know I can do better.

So, what’s stopping me? Maybe it’s the fact that every time I start diving into how to prepare, I immediately feel overwhelmed by the amount of gear I’m supposed to source. Maybe it’s that stocking up on these supplies isn’t cheap. Or, maybe it’s that I’m chronically ill, and thinking about all of this sends me into an anxiety spiral that I wouldn’t be capable of surviving a disaster scenario in the first place.

But, there’s another reason, too. There’s something about the survivalist mindset that has always made me feel a little icky. Like, if I actually dedicate my free time and money to investing in a survival kit, I’ll somehow transform into the worst type of “prepper”—dogged in my rugged individualism, determined that the end is nigh, and doomed to live a lonely life with my canned corn and conspiracy theories.

What is preparedness?

I don’t think I’m alone in these anxieties. In fact, even Marilyn Bishop, who runs a preparedness business, says she felt overwhelmed trying to get disaster-ready when she first learned about the Cascadia Subduction Zone in the Pacific Northwest. “I really wanted to prepare,” she told me. “But, it was not easy.”

Oregon, like several other states, advises that residents be ready to shelter-in-place for two weeks, and like me, Bishop found herself jumping from resource list to resource list, starting and stopping her preparedness efforts, and wishing there were an easier way. The experience motivated her to start Cascadia Ready, a company that curates kits based on state recommendations and individual needs, so you don’t have to do all the research and sourcing yourself.

For Bishop, preparedness isn’t just about major events like “The Big One.” It means thinking about the impacts of severe weather, long power outages, and other ongoing impacts of climate change. When she framed it this way, I realized I’m already “prepping” in ways I hadn’t fully acknowledged. I leave my air conditioner unit installed year-round, because heat waves can occur year-round here. I keep N95 masks stockpiled near my door, because I’ve lived through a pandemic and a climate disaster, and know there are more ahead. And, over the years I’ve amassed two large HEPA air purifiers in my home, which I adjust depending on the air quality.

So, despite feeling like I’m failing at preparedness, it turns out I’ve actually been slowly adjusting my behaviors over the years to account for both present and future threats— choosing a harm reduction approach over the overwhelm of perfectionism.

The term “preparedness” has come up most often in my work on pandemics. And, while many of the most crucial elements of pandemic preparedness require buy-in from governments (early access to diagnostic testing, investment in vaccine development, continuous stockpiling of personal protective equipment, and robust research and care for post-infectious diseases), individuals and smaller communities have also been doing their part by sharing the resources that are available, and normalizing risk mitigation behaviors.

This feels like a useful framework for combatting the overwhelm I’ve felt about other types of climate and disaster preparedness: Start small, work gradually, and—most importantly—prioritize community over individualism.

Let’s get logistical: building a kit

Sometimes, choice can feel daunting. But, I think there’s actually something empowering about approaching preparedness as a choose-your-own kind of adventure. And, according to Bishop, considering your own needs—while sometimes daunting (especially if those needs are medically complex)—is a crucial to surviving a crisis. “There’s [research] showing that people who thought through what they would do in an emergency—even if they didn’t do anything else—fared way better than people who never really thought about it,” she said.

So, let’s dive into some common needs, starting at the very beginning with what you need to get prepared. Here are a few common options that emerged in my research:

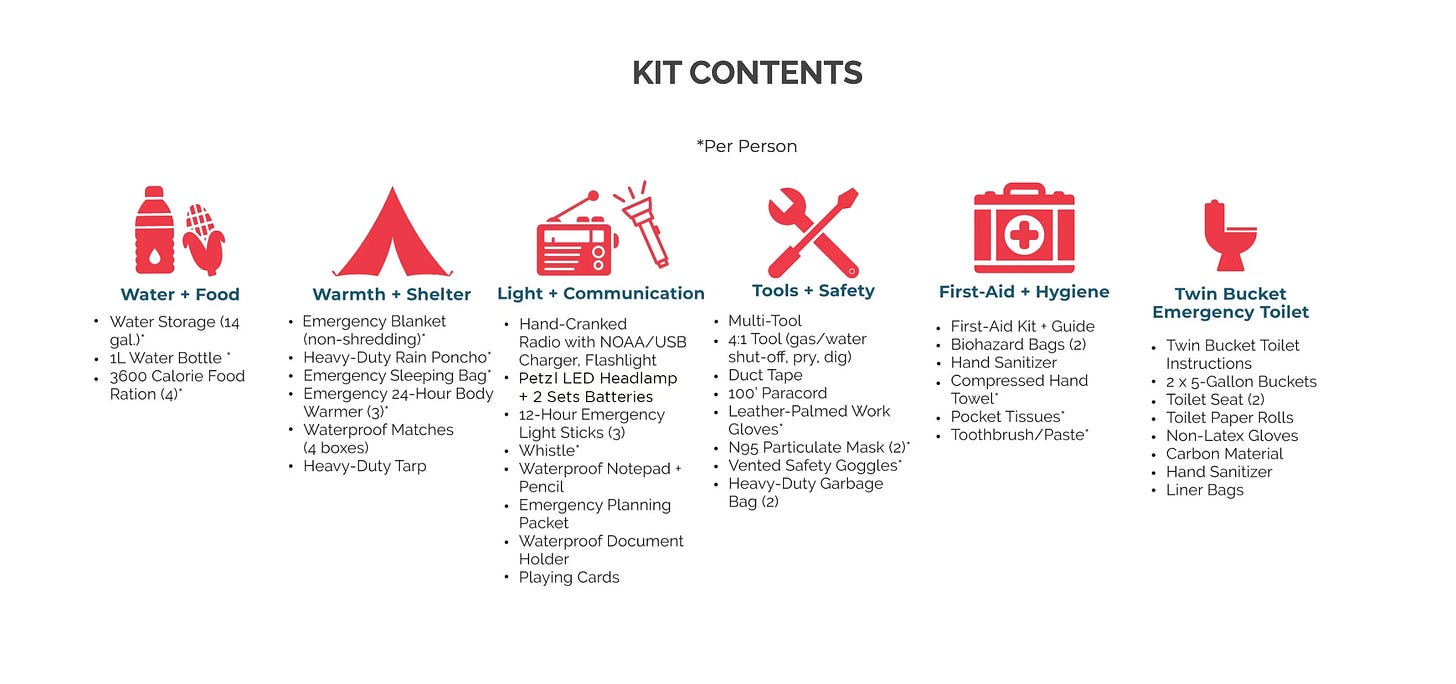

You need help gathering items: If, like me, your primary barrier to preparing for a climate, or similar, disaster has been the daunting task of figuring out exactly what you need from the various lists that exist on the internet, Bishop’s company might be a good fit. Her kits aren’t cheap (the one-person kits range from $360 to $1,099), but Bishop’s done the work of sorting through preparedness recommendations for you. Each kit contains water, food, blankets, first aid supplies, plastic sheeting, and an emergency hand-cranked radio, among other useful items. Cascadia Ready’s kits are built for earthquakes, but Bishop says they can help you through pretty much any other disaster (aside from nuclear war, perhaps). The kits also range in comprehensiveness, so you can buy one to supplement your existing supplies, or start from scratch.

You need to pace yourself: If your overwhelm stems from the time, money, and energy it takes to invest in preparing, you’re not alone. It can be exhausting and expensive to try to gather these supplies quickly. This is where gradual planning guides can come in handy. Bishop recommends Bainbridge Prepares’ Prepare in a Year program, which aims to get your household ready via a monthly plan. Each month provides an activity, and the tasks are ranked in order of immediate importance (step one is stocking up on water).

The Los Angeles Times’ “Unshaken” newsletter offers a similar approach, promising to get you earthquake-ready in six weeks. Each week’s installment focuses on a different aspect of preparedness, from checking your fire extinguisher, to making sure your pantry supplies haven’t expired.

Your medical needs feel daunting: If thinking about getting ready for a disaster feels overwhelming because daily life is hard enough as a chronically ill or disabled person, the problem (to be clear) is not you. Our healthcare systems do not make it easy to get what we need to live day-to-day, let alone prepare for two-weeks without access to medical care. That being said, assessing your current situation is a good place start. Here are some questions to consider:

What kind of disaster is most likely to occur in your area? This is a good place for anyone to start, to be clear, but if you’re chronically ill or disabled, it can be especially helpful to have a sense of whether you’re more likely to need to evacuate quickly or shelter-in-place. In some places, like earthquake and fire-prone L.A., you may need to prepare for both scenarios.

What medications would you be unable to live without? Arielle Duhaime-Ross, a science journalist, podcast host and disabled person who—as they put it—“naturally has an interest in disaster preparedness,” recommends asking your doctor to prescribe extra medications in advance of emergencies, or regularly trying to fill your prescription a little bit early so you can squirrel away a couple of extra pills each month until you have a stockpile.

What other foods or supplements are necessary for survival? For me, this means making sure I always have extra electrolytes on hand. For Duhaime-Ross, it meant sourcing shelf-stabilized food that won’t worsen their Mast Cell Activation Syndrome symptoms.

Do any of your supplies or meds require refrigeration? If so, can you amend your kit to include a small cooler, and ice packs you can grab from your freezer?

Does your disaster kit contain the right clothing to account for your needs? For example, I struggle with temperature regulation, so I tend to need more layers to feel comfortable.

If you use any assistive devices, can you buy duplicates? The answer is probably no, so here’s another idea that may be helpful: Create a shareable list of your devices, so that you and/or your support network can more quickly gather your things in the event of an emergency.

In a worst case scenario, like a symptom flare, how might your kit need to adjust? This question can feel frightening, so I want to pause here to acknowledge something that came up again and again in my conversations around preparedness: Any preparation at all is helpful, even if it’s not perfect. As Mother Jones disability reporter Julia Métraux shared in a previous installment of this newsletter, it’s better to be evacuated painfully, than to be left behind entirely. Duhaime-Ross has done a lot to prepare their household for disaster, but even they are aware of gaps. For example, they still haven’t tried any of the shelf-stabilized, seemingly MCAS-safe food they found to make sure it won’t cause a reaction. “That’s me putting my head in the sand,” they said. “I’m doing my best. We have food, and that feels like a win. It’s going to suck, but it should keep us alive.”

Who can you rely on for help, and have you practiced asking? I know from my own experience that it’s a lot easier to reach out for support during an emergency if you’ve already established a network of care. Bishop says your emergency support network should ideally already be familiar with your medical needs, mental health needs, and habits, so you don’t need to waste time going over the basics during a crisis. She recommends making sure at least one person has a key to your home, and both she and Duhaime-Ross emphasized the importance of knowing your neighbors—but, as Bishop put it, “even loose connections are good connections.”

If you’ve been reading this newsletter since its inception, it’s no surprise that I’m advocating for community as a resource in disaster planning. I’d also argue that disabled and chronically ill people—while often more isolated from neighbors and friends—are some of the most skilled community builders. But, before we dive into that further, it’s time to address the elephant in the room…

The problem of “the prepper”

In season three of HBO’s comedy series, The Righteous Gemstones, the show introduces a group known as the “Brothers of Tomorrow’s Fires.” Their camp is populated by rugged-looking white men dressed in camouflage, who clean animal skins and practice military drills. American flags mingle with confederate ones. “These folks are what you call ‘preppers,’” John Goodman’s character explains. “They believe the end is near and they don’t want to run out of toilet paper.”

While The Righteous Gemstones is known for its exaggerated humor, its depiction of prepper culture doesn’t differ substantially from my own understandings. Groups of white men prepare for a variety of different conspiracy scenarios—from alien invasions to white extinction—by living off the land and isolating themselves from perceived threats. Survivalism, individualism, and white supremacy have long seemed like comfortable bedfellows, and are often portrayed as such—sometimes as obviously as in depictions like the The Righteous Gemstones, and sometimes more subtly. In fact, theorist Mike Davis once argued that a majority of popular Los Angeles-based doomsday and disaster narratives are actually stories about racist fears.

At the same time, today’s survivalist movements have roots in historically progressive back-to-the-land movements, whose leaders argued against segregation, while promoting the benefits of homesteading as a solution to urban poverty, environmental health hazards, and other perceived dangers of industrialization. These earlier movements, which grew in popularity during the Great Depression and counterculture movements of the 1960s and 1970s might seem at odds with the white supremacist bunker brand of survivalism that dominates many mainstream representations today, but these people also also dealt in their own forms of supremacy—implicitly promoting white settler colonialism in their quest for land and natural resources, and sometimes veering into ableism in their desire to promote certain standards of health.

But, to write survivalism off as a purely white supremacist and individualistic ideology is to ignore:

The fact that marginalized communities are more likely to need to prepare for worst case scenarios, and thus often more likely to explicitly discuss preparedness.

The fact that preparedness can build community resilience.

Survivalism as community care

As disability activist, author and artist Maria R. Palacios told rabbi and disability scholar, Julia Watts Belser, “As disabled people, most of us are living in a constant state of survival.”

This can make it impossible to prepare beyond the given moment, but it may also mean disabled people are more inclined to practice a certain type of preparedness.

Palacios goes on: “I have a lot of friends who are disabled and undocumented, and…they survive because they know they need each other. This one makes homemade jello, this one knows who to call when the pipe breaks, this one’s husband is a wonderful mechanic…many of us have built our own networks through disability communities.”

Crip culture, as I’ve known it, is all about building these sorts of networks of care. As writer and educator Mia Mingus has written:

“As a disabled person, I am dependant [sic] on other people in order to survive in this ableist society; I am interdependent in order to shift and queer ableism into something that can be kneaded, molded, and added to the many tools we will need to transform the world…Interdependency is both ‘you and I’ and ‘we.’ It is solidarity in the best sense of the word.”

In my experience, this culture of interdependence—engaging in creative and continuous exchanges of care that go beyond the nuclear family—is perhaps the most crucial form of preparedness that anyone can engage in. It is the reason I was able to evacuate L.A. when the fires erupted in January, and that I was able to help others do the same. I’d argue that many marginalized groups excel at this type of “prepping,” because when every day involves some level of state abandonment, you gain some pretty key skills.

Marcia Alexander, the founder of Sustain Our Abilities, an organization focused on the intersections of climate change, health and disability, has been organizing events focused on helping people hone exactly this type of survival skill. Her “Day for Tomorrow,” events are meant to help communities prepare for climate change by fostering connection and conversation. By talking about what tomorrow might look like, communities deepen bonds that can help them better survive the present and the future. “Talking about preparedness for disasters helps you start learning about all these other things,” she said. “Just as important as having a go-bag is knowing who your neighbor is.”

When it comes to the more obvious aspects of prepping, like stockpiling supplies for your household, there’s an argument to be made that these actions can be community-minded, too. “If you are prepared, you are going to be less of a burden on the system that is very, very strained during an emergency,” says Duhaime-Ross. They’ve tried to stock up on extra supplies for the intended purpose of sharing with their neighbors. “For me, emergency preparedness is an act of love,” they said. “It’s community care.”

Bishop agrees. “It’s not just a personal step I’m taking by preparing,” she said. “The whole community resilience piece is part of the appeal.”

Safety pin

As I finished my research for this piece, I decided it was time to face the final boss: the “preppers” subreddit. Entering the belly of the beast, I was surprised to find that the forum was a bit less foreign than I’d imagined it would be. Users didn’t shy away from talking about climate change, and the first post I stumbled upon discussed how to prepare with disabled family members.

Were worlds collapsing, or had the rigid communities I’d imagined always been more porous than I’d understood? Maybe, the image of the conspiracist prepper (while accurate in some cases) has also been a way to write off inconvenient realities—like the fact that our societies are not adequately prepared for climate change, our marginalized communities are feeling it first, and our local governments are the ones who should be providing us with these preparedness kits.

“Maybe a decade or two ago, it was the ‘preppers,’ who had more of an apocalyptic view of the world, but that’s not really what most of preparedness is,” Bishop said. “We all live in places where we need to prepare for the worst, and hope for the best, and just keep moving.”

Her comment made me wonder if, when disaster hits, it really matters what you’ve been preparing for or why—and whether the pull of community might just be so strong that even those rugged individualists end up sharing some toilet paper. After all, in every crisis I’ve lived through so far, most people have drawn together, and only pulled apart once the government incentivized it.

I’m probably being too hopeful, but this possible reframing has felt helpful, lately. After all, I suspect my pessimism (about everything from my chances of survival to what survivalism implies) has been inhibiting my ability to actually prepare.

My survival kit still isn’t quite where I want it to be, but I’ve started envisioning it as more than a box of supplies. I guess I’ve begun considering: What if preparedness actually *is* the friends we made along the way?

Until next time, stay safe out there.

safety pin publishes approximately one-two times per month, sharing written and audio work on the intersections of climate change, chronic illness, and disability justice. If you value this work, please consider liking our posts, becoming a subscriber, and/or supporting by becoming a paid subscriber. Unfortunately this app doesn’t allow sliding scale subscriptions, so if you’d like to contribute at a lower fee than $5 per month or $55 per year, you can make a one time donation via venmo (@ fionalowenstein), or set up recurring monthly donations at Zelle (fionalowenstein@gmail.com). Funds go toward compensating our podcast producer, covering operational costs like Zoom and paid transcription services, and will hopefully allow me to eventually pay myself fairly for this work and bring in other talented trans and/or disabled collaborators.